INDIANA FISCAL POLICY INSTITUTE |

Commentary: Making population gains a pro-growth priority

Is Indiana’s local revenue structure stacked against fast-growing communities?

Hoosier politicos and policymakers often pay homage to Indiana’s pro-growth economic climate – referring to low taxes, an appealingly affordable cost of living and doing business, a focus on fiscal solvency and cautious attitude towards new regulatory burdens on employers.

But while Indiana’s policies seem to pay off in adding jobs, is our local fiscal structure ‘pro-growth’ when it comes to adding more Hoosiers? An upcoming analysis provides some compelling data to the contrary.

In many ways, Indiana is thriving: Consistently lower unemployment and higher workforce participation than the U.S. and neighboring states. In fact, Indiana is one of just ten states with an employment-to-population ratio (share of working-age adults with jobs) that’s fully rebounded from the Great Recession. 2019 was a record-breaking year in new capital investment for deals brokered by the IEDC.

But there’s one place Indiana is falling behind instead of setting the pace – building a bigger workforce to sustain our economic success. Our annual population increase has fallen behind the 50-state median over the last decade, and we rank 26th among states in total population growth since 2010.

Illinois and Ohio rank even lower than Indiana in population growth, but it’s easy to point to higher taxes and weaker job markets as likely culprits. Even grading us on a curve (national dynamics still favor the Sunbelt over the Midwest), our population trajectory is barely average.

There are many factors influencing demographic trends, but good reason to start the explanations with the governments closest to the people themselves: In the midst of efforts to create a pro-growth state for economic development, have we created an anti-growth climate for investing in local quality of life?

In a soon-to-be-released report for the Indiana Fiscal Policy Institute, Professor Larry DeBoer of Purdue University helps address this question by expanding an earlier study of how revenue capacity is keeping up with service costs for local governments across our urban, rural, suburban and industrial communities.

Professor DeBoer looks at taxable assessed value and income, state aid for schools and roads and other minor revenue sources to find ‘revenue capacity’ on a county-by-county basis. On the cost side, he uses per capita average local spending, adjusted to reflect city and town population, school enrollment, and miles of city and county roads.

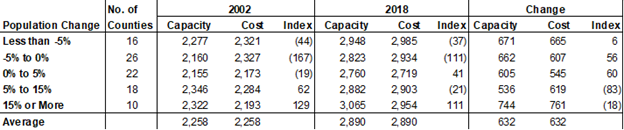

He distills all this into a single value – the Revenue Capacity-Service Cost Index – to compare fiscal conditions from county to county. A negative Index implies more pressure on local governments to raise taxes or cut expenditures, while a more positive result means flexibility to reduce tax rates or spend more. As part of the analysis, DeBoer compares a 2002 version of the Index to the latest data (2018).

His work will provide a wealth of insights for policymakers, among them what appear to be localized hurdles to strong and sustained population growth. Let’s look at changes in Capacity-Cost Index versus population:

Source: Larry DeBoer

From 2002 to 2018, 32 Indiana counties saw real population losses – but their fiscal climate modestly improved, with higher Capacity-Cost Index results. Another 22 counties saw slow-but-positive growth (less than 5%) and a more positive average Index.

But the 28 counties that boasted higher than 5% population growth had a collectively more negative Index. With residential development, revenue capacity was outstripped by cost – new infrastructure, higher traffic on existing roads, more kids in school and demand for public safety protection. The areas (mostly metropolitan) that drive population growth are also our most disadvantaged.

Looking to the future, Ball State economist Michael Hicks points out a persuasive trend in the U.S. Census Housing Survey data over the last few decades: Until the mid-90s, a plurality of respondents based homebuying decisions on work – people moved where the jobs were. Since then, the importance of good schools and public services overtook and then dwarfed job-related reasons. By 2013, these factors were seven times more likely than employment to be cited in relocation decisions.

In this context, the downside of a local fiscal structure that pushes our fastest-growing communities to raise taxes or cut services (or both) becomes more obvious. Population growth beyond a certain level may erode capacity to invest in the attributes that made these places attractive in the first place.

Population stagnation can’t compete with the coronavirus or a looming manufacturing slowdown as threats to Indiana’s economy. But as population growth has faltered, Indiana’s personal income and revenue collections have similarly lagged the rest of the U.S. – even our current recovery has been hindered by fewer wage-earners and taxpayers.

DeBoer’s research doesn’t purport to offer solutions. We may need to offer local governments greater flexibility under property tax caps while tackling the thorny political issue of too many overlapping local taxing units making claims on a limited base. It could be time to rethink how we distribute local revenues and calculate maximum levy growth, or explore new revenue streams (like local option sales taxes).

But following the data makes a solid case that our current system is inconsistent with pro-growth ambitions in a talent-driven economy, and local reforms deserve a higher place on our policy agenda.

Download a PDF of this commentary.